What is Machine Learning and how it works

Machine Learning and AI are a part of the technological revolution, which we’re right in the middle of. Everyone heard of ChatGPT at least once and all kinds of impacts it may have on our lives. Whether you’re an engineer or not, it’s a good idea to understand the basic idea of machine learning and AI.

Describing reality with properties

How do we describe reality? Let’s take the most simple example and imagine we want to describe a tiny black sphere (we’ll call it “the dot”) that’s placed somewhere around:

Easy. We can say it’s black, it’s tiny, it doesn’t smell, and things like that. These are object properties, where an object is our dot and property is anything that describes the object. But what if another dot is also placed somewhere near:

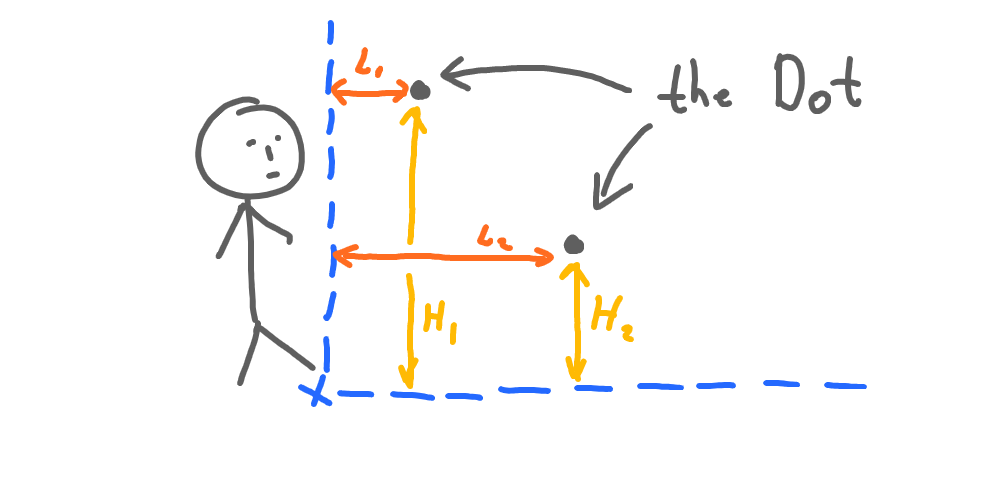

Now, we have to think about properties that differ between the two dots. They are identical in terms of weight and size (and smell). But different in the way they are located in space. Let’s take the distance from where we’re standing (horizontal distance, L) and distance from the ground (vertical distance, H):

So now we have two dots each described by two properties:

| Dot | Horizontal distance (L) | Vertical distance (H) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 2 |

| 2 | 3 | 4 |

Let’s imagine the following scenario:

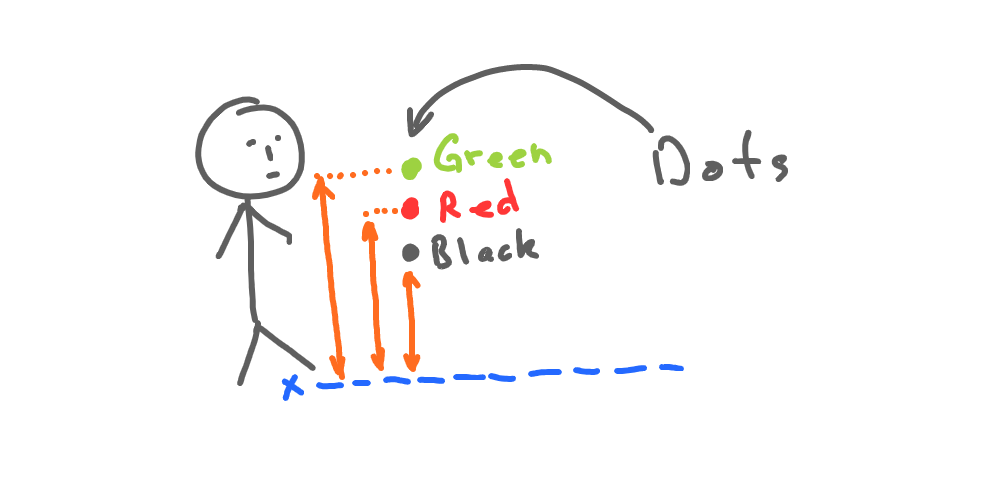

Now we have 3 dots of different colors, that are located at the same distance from us but a different heights:

| Dot | Color | Height |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Black | 2 |

| 2 | Red | 4 |

| 3 | Green | 6 |

We choose object properties to describe them in a particular situation. The same objects can be described differently for each specific case.

Intelligence

There are a lot of definitions of what intelligence is, but let’s simplify it to the following example:

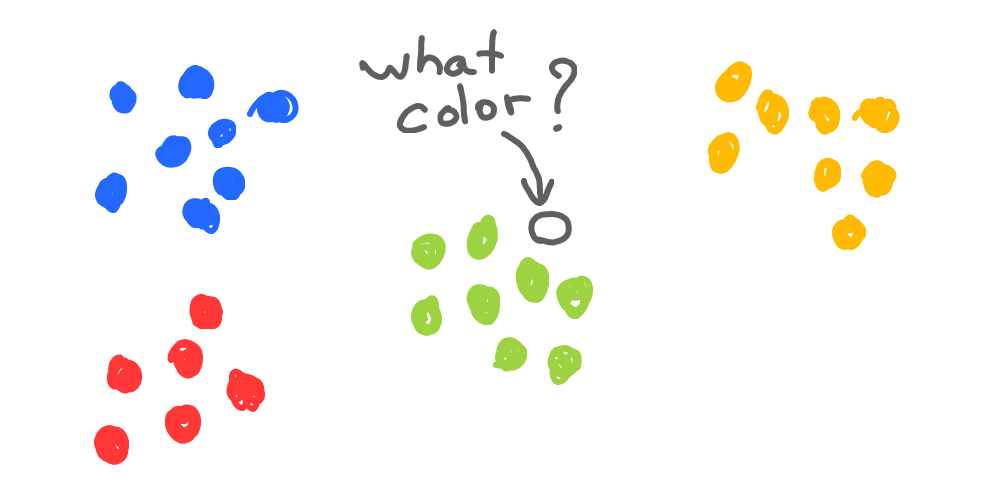

Without knowing anything at all about what those colored dots are, can you guess the color of the marked dot? Well, you can’t say for sure, but it looks like it should be green:

But how did you do that? You don’t know any context, description, or anything at all about these dots. Well, we can say, that based on all information that was provided, the color of the unknown dot is most certainly green. And our brain did quite a good job behind the scenes to come to that conclusion. The ability to do that is intelligence.

The most interesting is that we know how our brain did that and we can reproduce that with math and computers. So we build a program, that will give us the same result - guess the color of the unknown dot. And this will be artificial intelligence.

Math of Intelligence

We can generally describe the task of artificial intelligence as guessing the unknown properties of objects based on the given information. For example, guess the time it’ll take to get to the store by car based on the number of cars on the road. Or guess the chances a person will return his loan based on income and loan history. Or guess tomorrow’s weather based on millions of measurements collected by weather sensors.

How do we do it? With math.

Let’s take a simple example:

| Age | Number of friends |

|---|---|

| 8 | 10 |

| 9 | 15 |

| 10 | 20 |

| 11 | 25 |

| 12 | ? |

| 13 | 35 |

We have certain data, that show how many friends a person at a given age has. But unfortunately, the number of friends at the age of 12 is unknown, and we need to guess it.

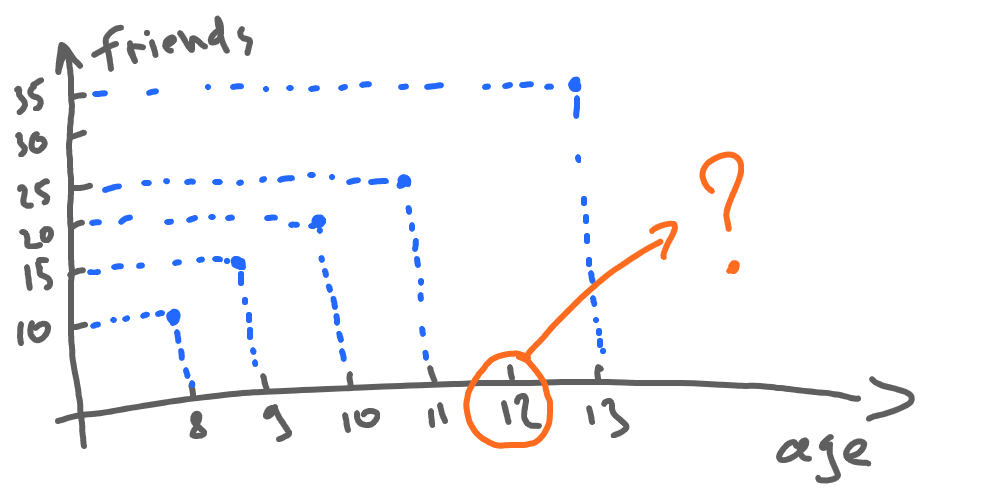

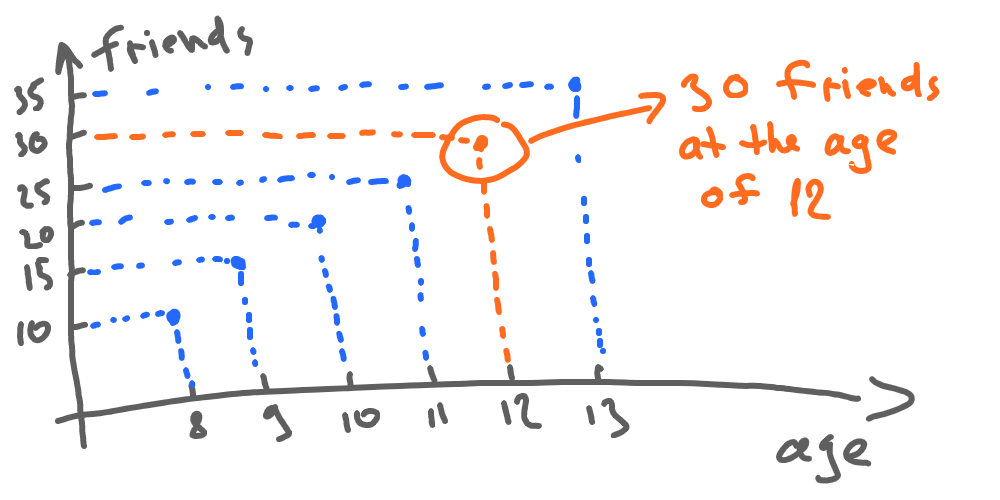

Let’s visualize this data by the following chart:

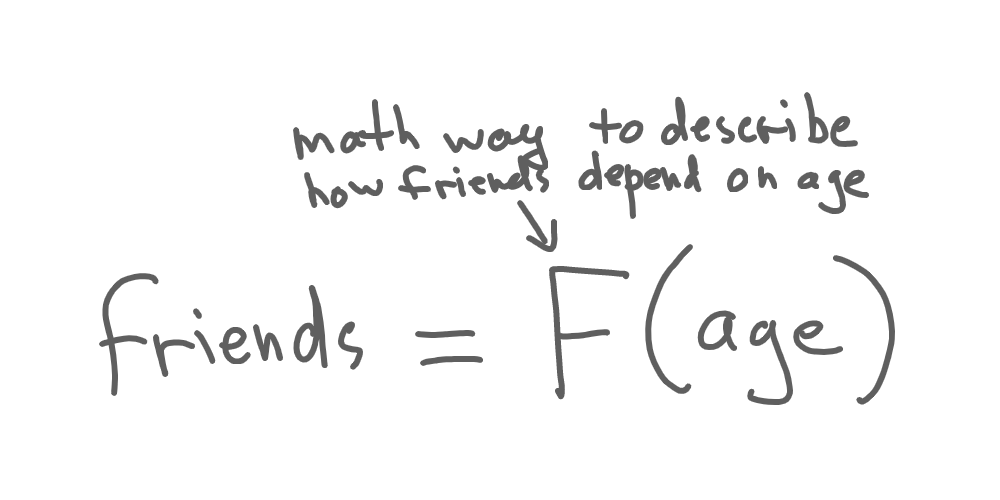

Math helps here by giving us a way to describe our data as a function. The function allows us to calculate one property (e.g. friends) based on another (e.g. age):

There are a lot of different methods to find out the function itself. Let’s just use the simple visual method at this time:

Given this function, we can now find out that the number of friends at the age of 12 is 30:

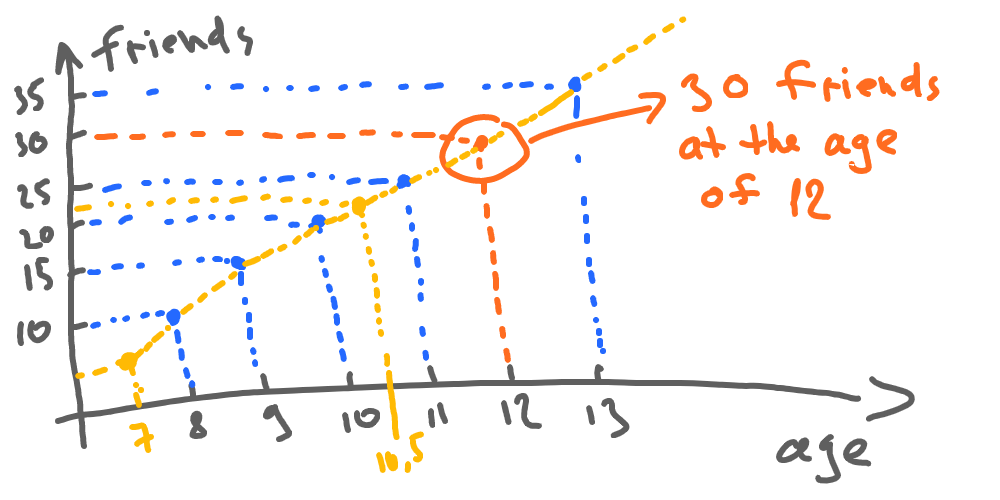

The described function friends = F(age) also allows us to guess (or predict, as machine learning guys call it) friends’ number for any given age, let it be 7 or 10 and a half. So we can pick any age value and calculate friends number based on our function (this is called continuous function):

Okay, now we have artificial intelligence that’s able to predict the number of friends based on any age we ask it to.

Finding functions using machine learning

Wait a minute… It’s cool that we have used the “visual” method to find our function (how friends depend on age). But it’s not artificial intelligence at all, we did it using our brains.

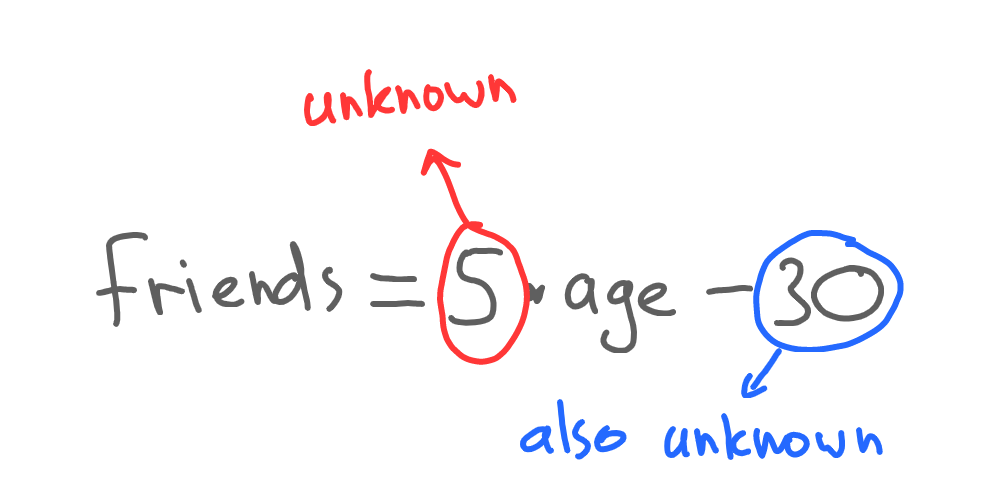

Yep, and that’s where machine learning enters the room. We did the tricky part when we defined those two numbers - 5 and 30:

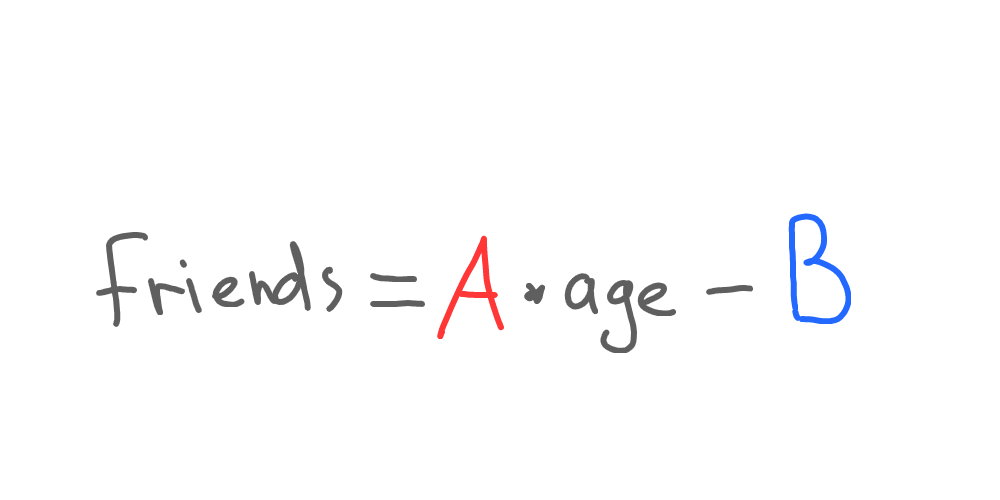

Let’s substitute those numbers with A and B respectively:

Now our function is unknown since we have unknown A and B (usually called coefficients) instead of calculated values. Next, we need to learn (or, to be more precise, we need our machine to learn).

Training and validation sets

The idea of finding coefficients is pretty simple. We just try values till we reach good ones. How do we define good ones? Great question. That’s why we need to split our data into two sets (datasets) - one for learning (training dataset) and one to check if our findings are good (validation dataset). It doesn’t matter how we do this at the moment, so let’s take the first 3 records as training and the rest of known records as a validation dataset:

| Age | Number of friends | Dataset |

|---|---|---|

| 8 | 10 | Training |

| 9 | 15 | Training |

| 10 | 20 | Training |

| 11 | 25 | Validation |

| 13 | 35 | Validation |

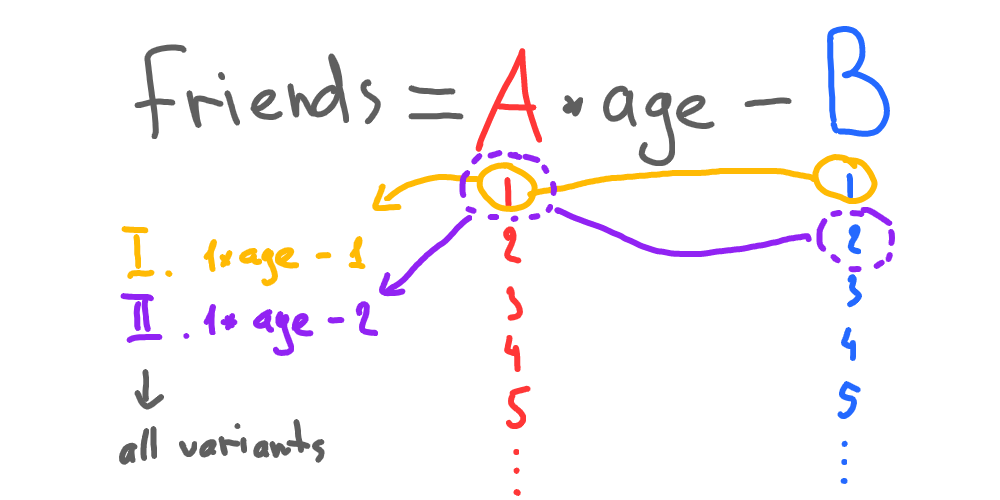

Now, we have to pick all possible A and B numbers for our function:

For each case, we find out how far the calculated value (number of friends) is from the real one:

| Age | Real number of friends | Got from  |

Got from  |

. . . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8 | 10 | 7 | 6 | |

| 9 | 15 | 8 | 7 | |

| 10 | 20 | 9 | 8 |

The numbers (of friends) we get from each function are usually called predictions. Now let’s find out how far our predictions are from real numbers for each function. This is also called an error:

| Age | Real number of friends | Predicted by  |

Error by  |

. . . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8 | 10 | 7 | 10 - 7 = 3 | |

| 9 | 15 | 8 | 15 - 8 = 7 | |

| 10 | 20 | 9 | 20 - 9 = 11 |

If we sum errors for each record, we can calculate the total error for each function we check:

| Function | Total error |

|---|---|

|

3 + 7 + 11 = 21 |

|

4 + 8 + 12 = 24 |

| . . . | . . . |

The idea of this learning process is to get the smallest (or zero) total error among all possible A and B values we check. So we just keep iterating till we find the following:

| Function | Total error |

|---|---|

| . . . | . . . |

|

0 |

| . . . | . . . |

This process might seem ridiculous, but our machines are capable of executing this kind of learning within a fraction of a second. Let’s program that using Python:

import time

start_time = time.time()

data = {8: 10, 9: 15, 10: 20}

variants = 0

for a in range(1, 100):

for b in range(1, 100):

variants += 1

error = 0

for age in data:

error += abs(data[age] - (a * age - b))

if error == 0:

print('A =', a, ' B =',b)

print('Variants checked:', variants)

print('Time took to learn:', round(1000000 * (time.time() - start_time)), 'microseconds')

breakA = 5 B = 30

Variants checked: 426

Time took to learn: 471 microsecondsdata— our training datasetrange(1, 100)— we limit values to check from 1 to 100variants += 1— count how many functions we’ve checkeddata[age]— the real number of friends from our training dataset(a * age - b)— calculating prediction of our function with currentAandBif error == 0— stop when the error is zero

That’s it. Now we have a function with calibrated coefficients (which is usually called a model in the world of machine learning). Note, that it took only 471 microseconds to train our model, meaning we could do a thousand of those learning procedures within a single second.

That is the logic behind machine learning. Not that hard, right? You just ask your computer to crunch numbers till the error is small enough. Then use obtained numbers (coefficients) to predict data.

Objects, properties, and numbers

Each piece of data (each row in our table) is usually called an object. Each column in our table stays for an object property. Each cell is a specific property value of an object.

There’s a lot of information around us but it all can be easily transformed into numbers. That’s why we can use math to work with any kind of data, be it text, images, audio, or video data.

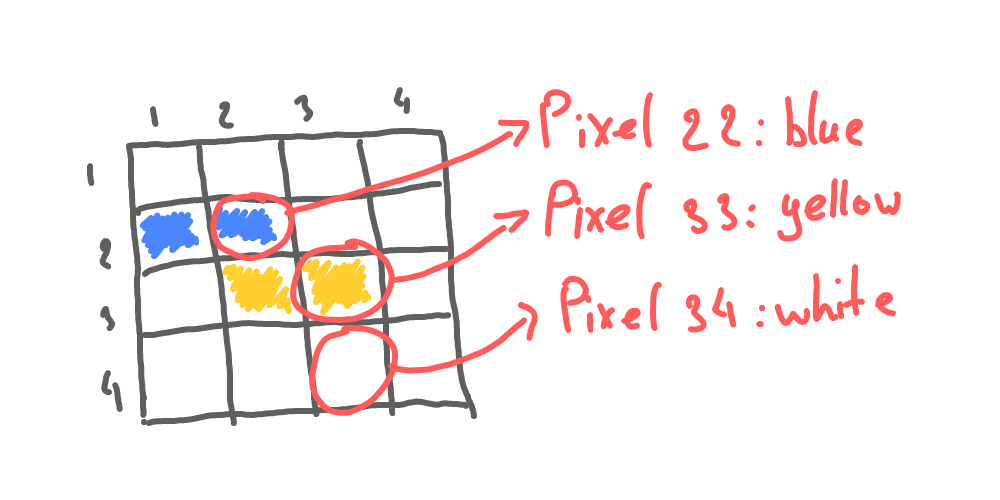

There are a lot of strategies to convert non-numeric data to numbers, but the concept is to have some sort of correspondence between original data and its numeric representation. For example, we can describe any image as a set of pixels (properties) with corresponding colors (or color codes - also numbers):

Machine learning in the real world

In the real world, we have everything a bit (or two) more complex, but that’s just a matter of details.

We usually have errors in data, so we must cleanse and prepare it before learning from it.

We also deal with a lot more than just a couple of properties (hundreds of thousands of properties are not so rare).

Real-world models can take a lot of time to learn because of complexity and data volumes, so learning optimization strategies are usually applied.

And there’s more, but still, the plan stays the same:

- Prepare data to train on, described as objects and their properties.

- Pick the best model (function) to fit the specific task.

- Train the model by iterating through coefficients and checking errors.

- Validate, tune, repeat.

Edit this article on Github